Kimono and Cultural Appropriation: The Positive Side of Appropriation and Misapplication of Fashion

A Look into the Kimono Wednesday Controversy at Boston Museum of Fine Arts

By Kaori Nakano

(Special thanks to Ms.Nikki Tsukamoto Kininmonth, and Prof.Shaun ODwyer, for the English version)

Between the summer and fall of 2015, “cultural appropriation” became somewhat of a buzzword in fashion news abroad.

It all began in July when the Boston Museum of Fine Arts was forced to cancel their “Kimono Wednesdays“ kimono try-on event, due to public criticism. The event was meant to celebrate the homecoming of a painting featured in the Japan leg of a traveling exhibition titled “Looking East: Western Artists and the Allure of Japan”.

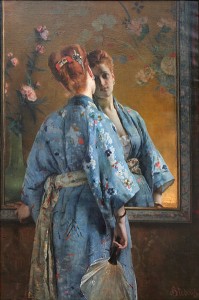

That painting, which was the center of the scandal, was Claude Monet’s La Japonaise, in which his wife, dressed in a bright red uchikake -a kimono robe usually reserved for bridal costumes- turns around to strike a pose toward the viewer. The weekly event was intended to attract visitors by offering patrons a chance to wear some similarly exquisite uchikake robes and pose in front of the painting for photos. Japan’s national broadcaster NHK, which had originally provided the uchikake to be tried on by patrons of the “Looking East” exhibition in Japan, had donated them to the Boston MFA to use and display as it liked.

It seemed like an event fit for the social media age; “try it on, take a selfie, upload and share.” But the event attracted guests of a rather unexpected kind – young and angry Asian American protestors bearing placards with slogans like “This is offensive to Asians” and “Cultural Appropriation”. Their message was also spread through fierce social media protests: Asian culture should not be stolen or superficially appropriated by a white supremacist culture.

On July 7, the BBC and New York Times reported the MFA’s announcement that it was cancelling the kimono try-ons (though Kimono Wednesdays continued). A new protest subsequently erupted, this time against the cancellation.

The counter protestors’ message in a nutshell was this: because very few Japanese were taking part in the original protests, the protestors were using the event as an opportunity to soapbox their views on Asian American identity. The counter protestors insisted that accusing Kimono Wednesdays of being a “white supremacist approach discriminating against Asians” was misguided, as the event had been organized through cooperation between Japanese and American parties, as a cultural exchange event.

It was Japan’s kimono industry and other related manufacturers that were potentially affected by these events, and a number of kimono designers have expressed their concern about it. Socially conscious Americans who admired the kimono began to avoid wearing it, from fear of being criticized for cultural appropriation. All this was occurring when Japan’s fast fashion retail company Uniqlo had just released their casual kimono wear and yukata lines for the global market.

The debate seemed to intensify as Halloween neared last year. Young Americans were now worried whether dressing up as a geisha would be cultural appropriation, and even I was receiving such inquiries, to which my response was; “Go ahead – dress yourselves up!”

On January 2016, Boston Museum held a conference concerning a serial debate, but the discussion there was very limited, dominated by identity politics rhetoric, and only one Japanese person spoke up and was critical. So I would like to comment on this case from a view point of fashion historian.

Let’s try to assume for a moment that wearing the kimono in disregard of how it was originally intended to be worn is indeed cultural appropriation. A perfect example of this would be the kosode gown, a traditional outerwear for men and women of samurai rank, brought to Europe in the 19th century and appropriated as room wear. For European women who had to wear a corset as part of their daily wear, the kosode gown was introduced as something more comfortable to slip into when relaxing in the privacy of their home. Looking up the English dictionary even today, the kimono will be described as “room wear” or “dressing gown” – a complete misapplication of the term.

However, it was Paul Poiret, a fashion designer of the early 20th century, who found inspiration in none other than this kimono for his corset-free dresses. Thus, the centuries-old custom of the corset diminished, allowing 20th century mode style in the West to blossom. Throughout history, fashion culture has developed via dynamic exchange between cultures. Through being cut away, or “stolen” from its original context (at times with misinterpretation), it leads to completely new and unexpected creations, which then later come back to their original culture as a new form.

This opinion may make more sense to contemporary Japanese, who have, without considering questions of their superiority or inferiority relative to other societies, welcomingly embraced various cultures. Japanese also usually feel rather honored to have their culture “appropriated”: David Bowie, the British superstar who left us recently, was very famous for “borrowing” his face paint, androgynous look and orange colored hair from Kabuki theatre, and Japanese people applauded him for doing this. But for people who still bear the scars from the dark days of segregation and oppression, having their culture “borrowed” on a superficial level does equal to appropriation. Even if it does not feel relatable to the Japanese, it is important to remember at the back of our minds that such thoughts still persist strongly in our world.

It is almost clear that people in Fashion industry does not care about which culture is inferior or superior. Fashion history so full of examples of “cultural appropriation” that it is even absurd to discuss about such tough question. We can hear the interesting comment from the people in fashion industry in the preview of upcoming documentary movie about Vogue, following the days leading up to the annual Met Ball . The 2015’s gala theme was “Chinese Whispers: Tales of the East in Art, Film and Fashion”. A lot of people expected the event and subsequent exhibition should be rife with racial insensitivity and cultural appropriation, especially in this mood around the Boston Museum. But, it seems the film doesn’t skirt around the tough questions. Only Andrew Bolton, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute curator, tells to the camera, “There’s a lot of political hurdles. Some of the topics that the exhibition is addressing could be interpreted as being racist.” And I am sure they will ignore all claims if they should occur, because it is simply “not fashionable” , or even nonsense, to take up such claims seriously.

As if to prove the feelings above, NY collection held in February 2016 acclaimed the Kimono Collection by Hiromi Asai. Models are western women, including colored people, who wore about 30 designs featuring colorful kimono of Kyo-yuzen dye and Kyo-kanoko shibori tie-dye accentuated with obi in Nishijin-ori brocade, which wowed the audience at the runway show. Ms. Hiromi Asai, the brand producer said; “We want kimono to become familiar with a wide range of people beyond the boundaries of culture and race.” And there occurred not a single discussion about appropriation.

(By courtesy of the producer, Ms. Hiromi Asai)

Something I saw recently in the news felt like a faint ray of hope amidst news stories riddled with darkness and despair – the gentle emergence of Muslim Lolita fashion within Islamic cultures. Young Muslim women are now “borrowing” the Japanese Gothic Lolita style and donning frilly pastel colored hijabs – and it is an incredibly cute sight to behold.

Personally, I simply see this movement as an expression of admiration for Japan’s Lolita fashion. Imagine if no culture was considered superior or inferior to others, and if dark histories of our past were not brought up each time we wished to casually “appropriate” each other’s styles, simply because we admired and adored them. I think “appropriation” of fashion can be one of the most direct and loving ways of saying “yes” to another culture.

Responding to the love call from Muslim women, Uniqlo has teamed up with Muslim fashion designer, Hana Tajima, to create a modest ‘lifewear’ collection for women, which includes traditional wear like kebaya and hijabs. It seems to me this is one modest and modern step of the cultural infusion through fashion, which will lead us to understand each other.

I wonder, or rather pray, that sharing such a sense could one day make this world a more peaceful place.

(Alfred Stevans, La Parisienne Japonaise. 1872. From Wikimedia Commons)

Kaori Nakano is a fashion historian and professor at Meiji University in Tokyo.

返信を残す

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!