ボストン美術館の「キモノウェンズデー中止事件」。日本のメディアではなぜかほとんど報じられなかったのですが、海外、そして日本の中での海外コミュニティでは議論を巻き起こしています。

フェイスブックページも立ち上がり、私も参加して議論を見守っていたのですが、そのページにお招きくださった国際日本学部の同僚、ショーン・オドワイヤー先生がジャパン・タイムズにとても文化的な配慮の行き届いた記事を書きました。「キモノと文化の借用について」。ショーン先生と議論をしたなかでの私のコメントも最後の締めに引用してあります。光栄です。

以下、ショーン先生の論文のきわめて大雑把な超超訳です。きめこまかなニュアンスに関しては、Japan Times の原文をあたってください。

★★★★★

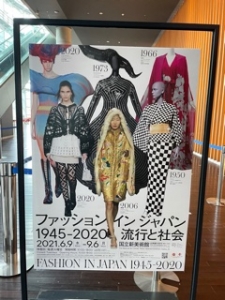

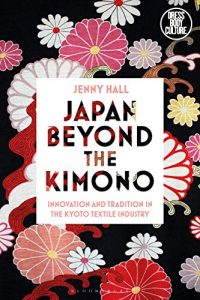

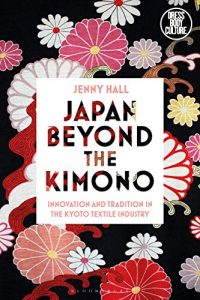

キモノ産業はずっと衰退に向かっている。だからキモノ産業は主流である伝統的なフォーマルなキモノだけではなく、海外のマーケットに目を向けている。

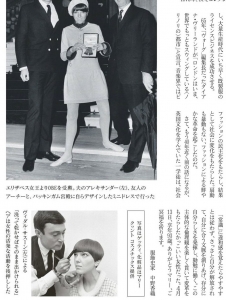

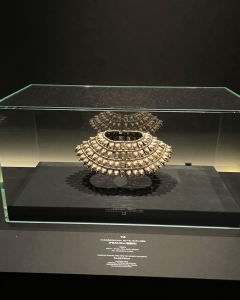

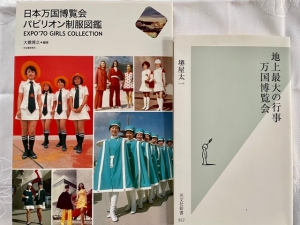

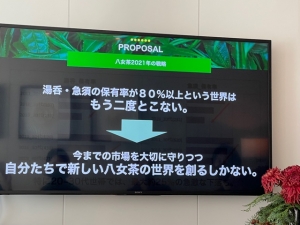

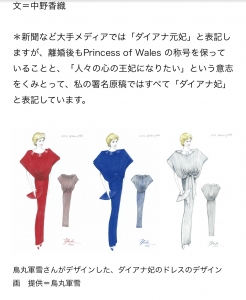

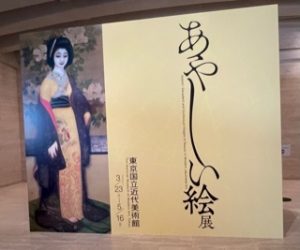

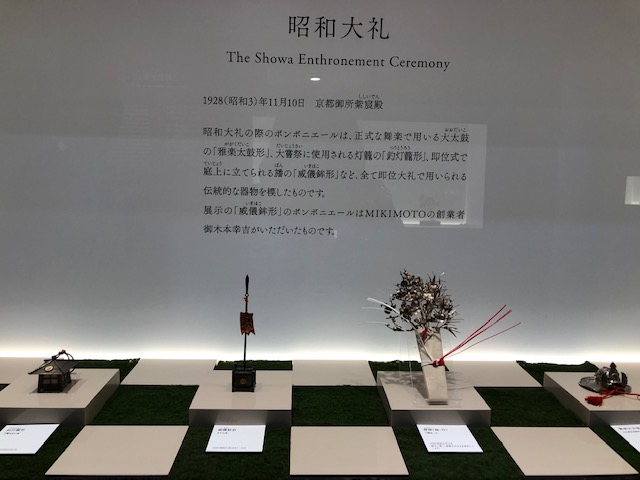

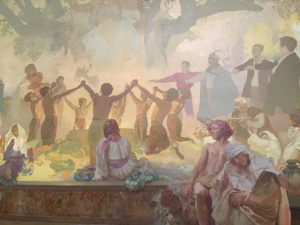

最近、ボストン美術館がおこなった「東方を見る:西洋のアーチストと日本の魅力」展は、NHKも協力し、キモノ文化のプロモーションという役割も担っていた。

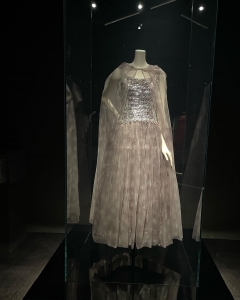

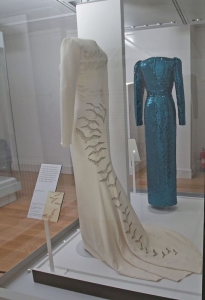

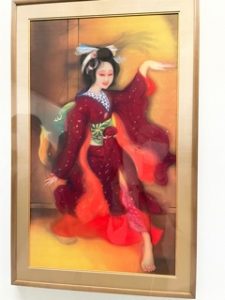

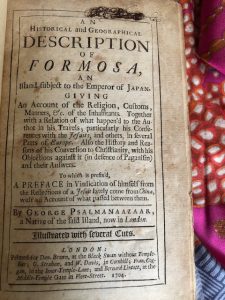

1876年にクロード・モネが描いた「ラ・ジャポネーズ」。モネが自分の妻に打掛を着せて見返り美人のポーズをとらせているが、当時のフランスにおけるジャポニスムの熱狂を皮肉ったものでもあった。

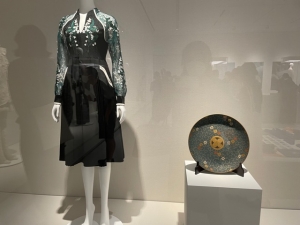

ボストン美術館はキモノ・ウェンズデーを企画。来場者は、モネの絵に描かれたような豪華な刺繍を施された打掛(用意したのはNHK)を着て、絵の前で写真を撮ることができるというイベントである。

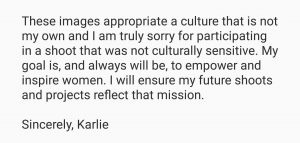

ところが予期せぬ出来事が発生。アジア系アメリカ人と思われる若い抗議団体がプラカードをもってキモノ・ウェンズデーにやってきたのだ。「オリエンタリズム」「人種差別」「(アジア人を侮辱する)文化の勝手な流用」と。

抗議団体はフェイスブックページを立ち上げた。「Stand Against Yellowface」。そのほかのソーシャル・メディア上にも、エドワード・サイード(「オリエンタリズム」の著者)のへたくそなカラオケのような宣言を書き連ねた。白人至上主義的なやり方でアジアの文化を勝手に流用するなというような、美術館に対する批判が続いた。

7月7日、美術館はキモノ・ウェンズデーのイベントを中止。BBCとニューヨーク・タイムズがこの経過を報じると、こんどはイベント中止に反対するカウンター・プロテストが起きた。

カウンター・プロテスター(抗議団体に反対する人たち)の議論はこのようなもの。抗議団体のなかに日本人はいない(おもに中国系)。抗議者たちは、アメリカにおけるアイデンティティを主張したいがために、このイベントに場違いに乗り込んだのだ。

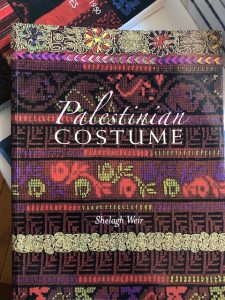

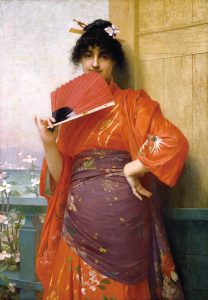

また、サイードの「オリエンタリズム」も誤用されている。サイードの議論は、19世紀から20世紀の西洋のアーチストが、中東やアフリカ社会を自分たちの植民地として帝国主義的な目線(上から目線)で表現していたというもので、その文脈における文化の借用・流用はたしかに非難されるべき「文化の盗用」であった。

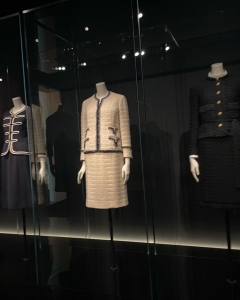

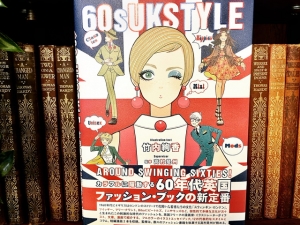

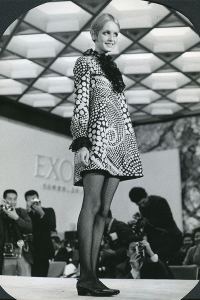

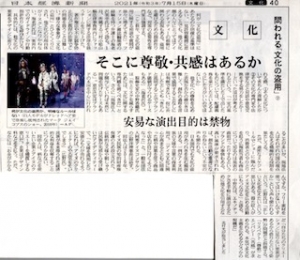

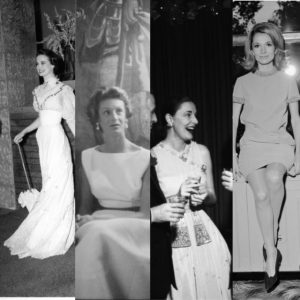

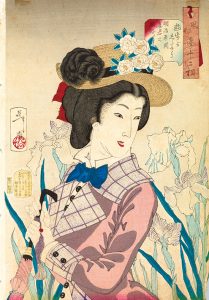

しかしサイードの議論は日本やアジアにはほとんどあてはまらない。20世紀の初期、フランスのデザイナーたちは「流用した」キモノスタイルから西洋の女性のためのドレスを作り、日本のテキスタイル産業はこのトレンドを非常に喜んで受け入れた。

そのころは日本もどちらかといえば帝国主義的な力をもっており、「西洋化」の視線さえもって西洋文化を見ていたので、西洋が日本の「エキゾチック」な絵やファッションに熱狂したということは、サイードのオリエンタリズム論にはあてはまらないのだ。

現在のキモノ・ウェンズデーは、日本とアメリカが協働しておこなった文化交流のイベントであり、それに対して「白人至上主義目線から見たアジア人蔑視」というオリエンタリズムの議論をふりかざすのは、滑稽きわまりない。と。

しかしそもそも、こんなアカデミックな議論などここに関わってくるべきではないのだ。もっとも懸念されることは、こんなことが起きることで、キモノ産業の将来の頼みの綱である海外市場が閉ざされてしまうこと、なのである。いまやユニクロも浴衣やカジュアルキモノを世界中で売る時代。「白人が着物を着る」ことにオリエンタリズム云々の議論を持ちこむことはまったくナンセンスである。

さらに興味深いのは、世界中のメディアがこれだけ騒いでいるのに、日本の主流メディアがほとんど話題にしていないこと。日本国内の文化人やファッション関係者もほとんどこの問題はスルーである。

そもそも、「キモノを試着することが人種差別であり、帝国主義的である」という発想じたい、日本人にとってナゾなのである。「抗議団体は、反・日本の立場をとる中国・韓国系の扇動者だ」とする右翼系の愛国者もいる。

おそらく、多くの日本人にとって、このような議論はまったくピントがずれているようにしか感じられないのだ。多民族国家アメリカの中での人種間の小競り合いなんだろうな、くらいにしか見えていないのだろう。しかし、浴衣に魅力を感じながらそんな繊細な社会問題にも気を配り、ほんとうにキモノを着ていいのかどうかためらってしまった良心的な外国人のためにも、今こそ日本側からはっきりしたメッセージを発することが必要だ。

そのメッセージを、京都の西陣織工房で働くある雇用者から受け取った。「だれでも、いつでも、いかようにでも、キモノは好きなように工夫して着てかまいません」

日本は西洋に虐げられた植民地だったわけではない。キモノ産業は、オリエンタリズムに対する固執と政治的に正しい「理解」とやらによって、かえって迷惑をこうむっている。このことはもっと広く伝えられなくてはならない。

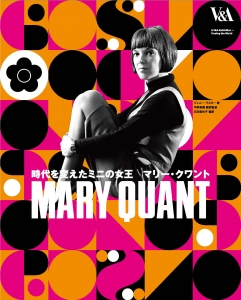

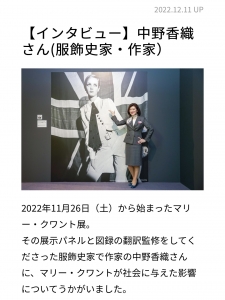

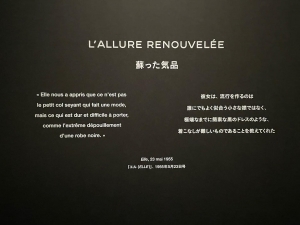

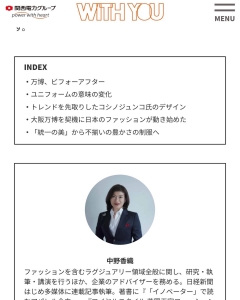

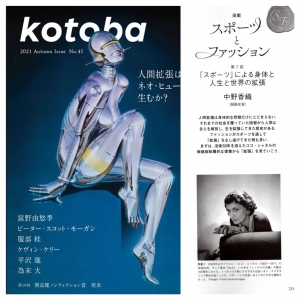

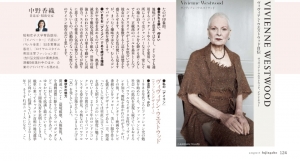

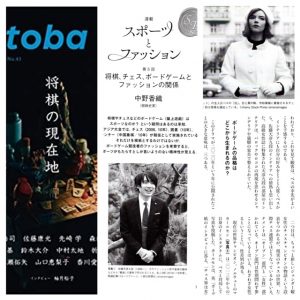

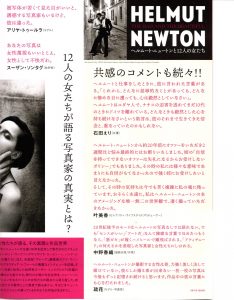

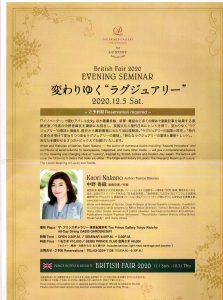

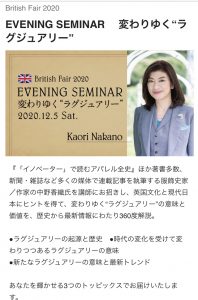

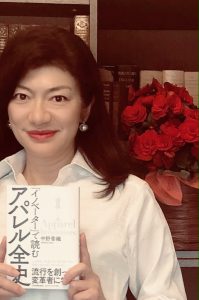

明治大学でファッション文化史を教える中野香織・特任教授はこのように表現する。「文化の借用は新しい創造の始まりです。たとえそこになにか誤解があったとしても、その誤解から何か新しいものが生まれます」。このように受けとめることがキモノファッションの未来を開くカギになるだろう。

★★★★★

最後の引用は、ショーン先生とのメールのやりとりのなかで伝えた言葉です。”Cultural appropriation is the beginning of the new creativity. Even if it includes some misunderstanding, it creates something new.”

Shaun-sensei, superbly well written! Thank you for citing my words in such an impressive way. I am so proud.

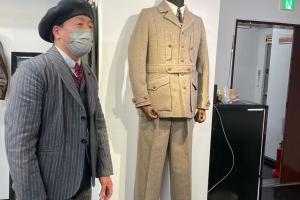

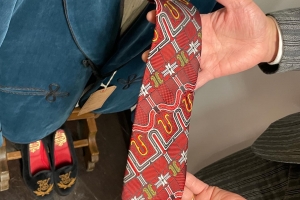

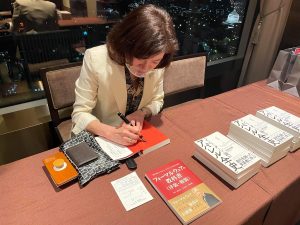

パリを中心に活躍するアーティスト、ナタリー・レテさんとのコラボもあり、私もコラボの羽織を羽織ってみました。ふつうに洋服の上から羽織って違和感ありません(……よね?😅)

パリを中心に活躍するアーティスト、ナタリー・レテさんとのコラボもあり、私もコラボの羽織を羽織ってみました。ふつうに洋服の上から羽織って違和感ありません(……よね?😅) 写真下の振袖もNADESHIKOです。シックでかわいい、個性的な振袖で、普段着としても着用可能。

写真下の振袖もNADESHIKOです。シックでかわいい、個性的な振袖で、普段着としても着用可能。

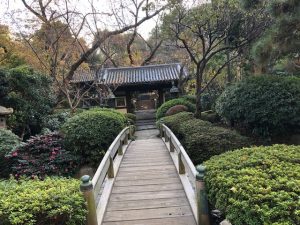

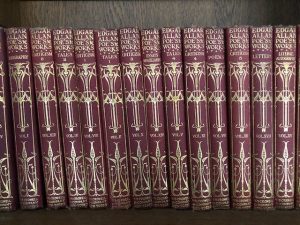

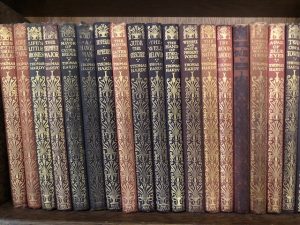

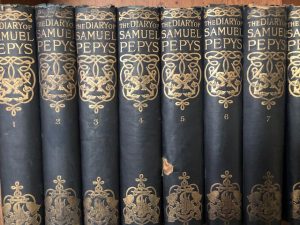

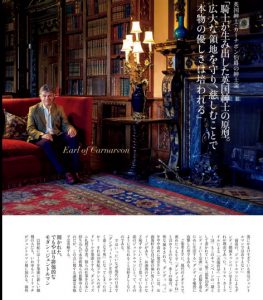

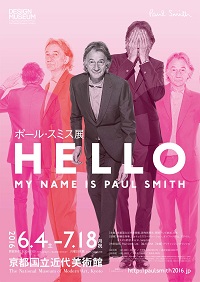

ご参考までに「イギリス館」とは。

ご参考までに「イギリス館」とは。

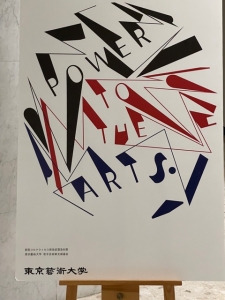

異文化リテラシーがますます重要になっていくこと

ファッションが農業と結びつかざるを得なくなっていくこと

政治(労使関係、国際政治問題、人権)との関わりを考えることがファッションにとって必須になっていくこと、など。

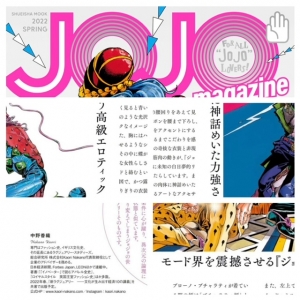

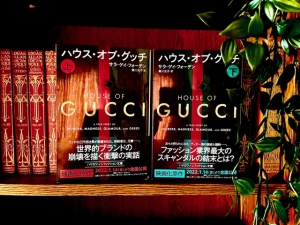

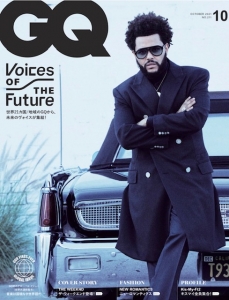

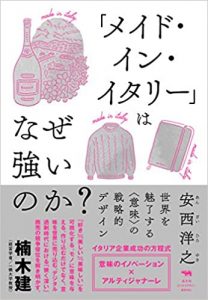

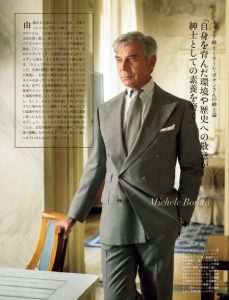

LVMHプライズの審査員として初回から関わり、世界の状況を肌感覚で知る第一人者としての栗野宏文さんに世界の話を、ヨーロッパ、とりわけイタリアの実情をリアルに知る安西さんの話を、中野が聞いてまとめています。ユナイテッドアローズの商品の話には一言もふれていません。国内でのビジネスもここでは一切議論にあげていません。世界に照準を据えて、スタートアップを考える方はぜひご一読ください。